The following personal account of the Battle of Beja is taken from the book Over to Tunis by Howard Marshall which was published in 1943.

Beja is a charming little white town on a hillside some twenty-five miles north-west of Medjez el Bab. Just behind it is a ruined castle, and standing on the summit of the castle, listening to the French plane spotters at work, and looking towards Tunis, you could see two broad valleys stretching eastwards. One swung north to Djebel Abiod and Mateur; the other vanished between steep, rounded hills towards the railway station of Ksar Mezouar and the famous Hunt’s Gap. White roads threaded the valleys, roads along which the Germans were pressing with tanks and infantry from the direction of Mateur.

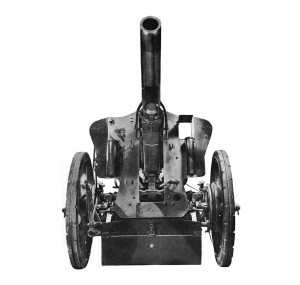

Brigade H.Q. at that time were established in a tiny railway station up the Hunt’s Gap road, about three miles from Beja. When you drove up towards them, leaving your car carefully camouflaged in a field some distance away, the crack of our 25-pounders would shatter your eardrums as they shot over the hills at the advancing enemy.

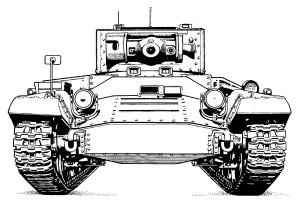

The situation at first was very obscure. We could not be certain of the full strength of the German attack. There were rumours, the first morning I went up there, of forty German tanks roaming somewhere over the brow of the hill, tanks which might appear at any moment. There were, it was thought, some eighty tanks working up the road itself in the Hunt’s Gap direction, and our Churchills had gone out to prospect.

It was a typical Tunisian action. Brigade H.Q. hummed like a beehive. The brigadier, in his truck, hidden and camouflaged under the eucalyptus trees, plotted and studied the ebb and flow of the battle. The colonel, wearing corduroy trousers and several sweaters, with a map case slung round his neck, listened to the reports coming in constantly, and issued his orders. The tanks were jockeying for position: nosing up the valleys, avoiding the skyline, trying to lure their opponents into the open within range….

Our Churchills, at all events, were maneuvering for position in the hills on either side of the Beja-Mateur road, and they were outwitting the Germans, who used their own tanks as decoys, and hoped that we should walk into traps. We had learnt a thing or two about that, however, and we kept hulldown, and shot at the enemy over the ridges of the hills, with strong support from our artillery.

It was a strange battle to watch. I saw our 25-pounders firing up the valley, and every now and again Messerschmitts and Stukas would swoop in to bomb and machine-gun our positions. From a slit trench half full of water I saw twenty enemy planes at midday circle over little Beja, bombing it viciously…. And all the while at Brigade H.Q. reports were coming in: eight German tanks destroyed–four infantry attacks repulsed–German tanks withdrawing under the fury of our artillery fire.

The news was not always as good as that. Indeed, it was often threatening and serious. The Germans were pressing hard, bringing up more tanks and infantry. For three days we expected to see them break through the last gap in the hills before Beja. We had knocked out at least twenty of their tanks, as we knew from our sappers, who went out, sometimes in broad day, to complete the destruction. But forty more were battering their way between the hills. They reached Ksar Mezouar station, about ten miles from Beja. They took the ridge of a hill which dominated the dip in the valley where our Churchills lay, and the Argylls were sent in to drive them off it.

The tank regiment colonel at Brigade H.Q. was worried. The German Mark VIs were proving an awkward problem. He did not know whether he could hold the weight of armour opposed to him. It was a brilliant day after heavy rain–rain, which, as we afterwards discovered, affected the result. He peeled off one of his sweaters, with a perplexed frown on his face, and then pored over his map again. His tanks had fought superbly. The infantry were holding firm. The guns in the field nearby were hammering away. The situation seemed reasonably sound, and yet there was something ominous about it, a feeling that at any moment the dam might break and the Germans come pouring through.

All day the feeling persisted. Perhaps it was strain and weariness which created this mood of depression. Then came a piece of news, late in the afternoon. A concentration of German tanks were reported near Ksar Mezouar. The 25-pounders opened up again with a wrathful bellow. When their shoot finished, it was seen that the German tanks were lying still, with their turrets open.

A tank officer went carefully forward to investigate. No shots greeted him. He reached the tanks, and looked into them. They were empty, deserted. The German crews had been unable to face our gunfire.

That was the end of the attack on Beja. Our 25-pounders had smashed the Germans back. Prisoners admitted that the pounding they had taken was too much for them. Some of them had been on the Russian front, and they said that never had they known such gunfire.

That evening, immediately we heard of the deserted tanks, I walked in the dusk up the road past Ksar Mezouar station, where the Germans had been an hour before. I passed some of our own tanks returning to harbour, jubilant at the swing of the battle. And on a hillside, blazing fiercely in the darkness, I saw a German Tiger, hit fair and square and utterly destroyed, a symbol of this sudden and most necessary victory.

Later, further along the road towards Sidi Nsir, I saw one German tank after another, twisted and shattered and burnt out. The weather had helped us. After the German attack began heavy rain fell, and the tanks had not been able to operate far from the single road, where our gunners and Hurricane bombers caught them. And as they withdrew the guns and the bombers harried them and chased them and hit them and gave them no rest.

This was not a battle on a large scale, but the Germans lost over forty tanks, and two out of the four German battalions of infantry were taken prisoner, in addition to the killed and wounded. Strategically it was most important. The loss of Beja would have meant a readjustment of our line along the whole northern sector, including a withdrawal from Medjez el Bab, and therefore serious delay to the entire campaign.

For a battlefield tour to these sites see http://www.western-desert.co.uk

Hey…thanks for that. Great post. I’ll be coming back.

Excellent site

Thanks for sharing. I enjoyed reading your article!

Good job on the site.

Remarkable post as usual.

my father 172 reg 155 battery have beja badge and war office reg he fired 25 pounders with scg henderson told very rare indeed help needed 01842 879219

My grandfather fought in this battle and also has a Beja badge. Apparently the c.o had these badges made for his men and are not recognised as official medals. Very interesting read. Thanks