The following article was printed in the December 1945 issue of C.I.C. (Combat Information Center) published by the U.S. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

The long, violent history of this war saw the rise of many new or radically improved weapons, from the magnetic mine in the early days to the “personnel-controlled bomb” (suicide plane) of recent fame. The story of Allied countermeasures to the threat of Axis weapons is in many cases as dramatic as the weapons themselves.

For instance, take the case of the German radio-controlled bomb. As early as 1941 British Intelligence began receiving reports that the Germans were developing a bomb which could be remotely controlled from a parent aircraft. Development and operational use, however, are two different things, and it was not until August, 1943, that the Luftwaffe was ready to unveil it. A group of corvettes on anti-submarine patrol in the Bay of Biscay were attacked by what was identified as a remotely controlled bomb—a missile resembling a small fighter plane—capable of radical maneuvering both in azimuth and elevation. The parent aircraft were DO217 twin-engined bombers. One of the corvettes was sunk, another damaged. Later in August further highly successful attacks were made against shipping in the Mediterranean and Bay of Biscay. The bomb (designated HS293) was released by the parent plane at altitudes of 3000-5000 feet and ranges of three to five miles from the target. The missile was jet-assisted shortly after its release; its speed, variously estimated at the time, is now known to have been about 325 knots. The controlling operator in the plane was able to follow the bomb visually by observing a light in the tail.

During and immediately following the Salerno landings the German guided missile program moved into high gear. The enemy introduced another type of controlled missile, the FX, a radio-corrected 4400 pound bomb of tremendous power and accuracy, as anyone present in Salerno Gulf at that time will testify. The Luftwaffe caught units of the Italian Fleet racing to reach Allied ports and scored heavily with both HS293 and FX bombs. They attacked Allied shipping in Salerno Gulf, sinking and damaging several British and United States warships, large and small. It was estimated that nearly 50% of the bombs launched were hits or damaging near misses.

At that time radio control was suspected (on the basis of prisoner-of-war reports) but was by no means confirmed. The control hand was supposed to lie in the 20 Mc region, and desperate, hastily improvised jamming effort was concentrated in this band, which seemed to improve morale without affecting the accuracy of the missiles.

TWO DE’S SEEK THE ANSWER

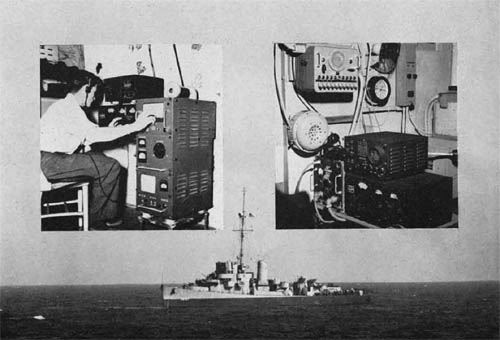

Meanwhile two U.S. destroyer escorts were fitted out with special search receivers covering the entire radio spectrum from 15 kc. to 3000 Mc, panoramic adaptors, recording and photographic equipment, and jammers (constructed by the Naval Research Laboratory) to operate from 10-35 Mc.

The mission of the two DE’s was two-fold: (a) to find and record the frequencies and modulation for control of the bombs, and (b) to jam them.

The ships selected for this ticklish assignment were the USS FREDERICK C. DAVIS (DE 136) and the USS HERBERT C. JONES (DE 137). RCM teams, specially trained at the Special Project School, Radio Material School, Anacostia, D.C., were placed on board each ship. The teams consisted of one officer, two technicians, two operators, and two photographers.

The two ships crossed the Atlantic at high speed, holding frequent intercept training drills on the way, and reported to Commander U.S. Eighth Fleet on 15 October 1943. The ships were formed into a special task group and ordered to escort duty along the frequently attacked Gibraltar-Naples convoy lane, the most vulnerable stretch of which ran along the North African Coast between Oran and Bizerte, within easy range of aircraft operating from bases in Southern France.

German aircraft, using torpedoes and radio controlled bombs, attacked a convoy off the Algerian coast at dusk November 6. The F. C. DAVIS and H. C. JONES, present in the screen, logged transmissions in the 48-50 Mc band coincident with visual observations of guided missiles being launched. On November 26, during a two-hour attack, reportedly one of the heaviest ever launched against an Allied convoy in the Mediterranean, about 20 control signals were heard. Both ships, having rebuilt their jammers to cover the 48-50 Mc range, jammed many of the signals, and topside personnel stated positively that several bombs went out of control when jamming was applied. The H. C. JONES postponed jamming long enough to record one control signal, and from information obtained the laboratories were able to design suitable modulators for the high-powered jammers then being rushed to completion at the Naval Research Laboratory.

Two of these transmitters—one kw. output—were flown to the Mediterranean and installed in the two DE’s prior to the Anzio landings in late January, 1944. At Anzio the Luftwaffe struck and struck hard, with glider bombs as well as high level and dive bombing attacks. The DE’s, the only ships then fitted with effective jammers, were necessarily retained in the assault area through the long weeks over which the attacks continued. As Task Group 80.2 the ships underwent more than seventy-five air attacks in forty-eight days, earning official commendation in dispatches from CominCh and Commander Eighth Fleet. During this period more than one hunclred guided missile signals were intercepted and jammed—not with complete success, apparently, for several ships were hit by these bombs. No U.S. warship was hit, however, and the percentage of hits was sharply reduced.

By the early spring of 1944 six more high-powered jammers had been completed in the United States, and two had been constructed by RCM personnel of the Eighth Fleet. These jammers, together with intercept receivers, were installed in four Eighth Fleet destroyers and minesweepers. All guided missile countermeasures personnel were organized into a single organization, CM Unit Z, comprising twelve officers and about forty technicians and operators. From this unit small teams of officers and men were placed on board the jammer equipped ships. Such ships were designated by the Commander in Chief. Mediterranean, as “J” ships and from one to three “J” ships were ordered as additional jammer escorts for all important convoys through the Mediterranean.

JAMMING STOPS THE BOMBS

From the time the “J” ship escort system was placed in effect no ship was hit by radio controlled bombs in convoys guarded by “J” ships, although many convoys were attacked during the spring and early summer of last year. One “J” ship was sunk by torpedoes in April and another damaged by mines during the invasion of Southern France.

The design of suitable jammers and jamming techniques was greatly assisted by the capture of several unexploded HS293 and FX bombs, in various stages of repair. Investigation under battle conditions was continued, however. Because of the difficulties of jamming and investigating simultaneously, a minesweeper, USS SUSTAIN (AM 119) was equipped with monitoring and analyzing equipment and accompanied convoys likely to be attacked and all invasion forces. Considerable additional information was obtained in the form of recordings and photographs which were analyzed by the Naval Research Laboratory. In addition, Countermeasures Unit Z maintained a laboratory and workshop in Oran, Algeria, from which installation, repair, and training were conducted.

Left: Medium powered jammer for guided missiles, with RBK receiver and RBW panoramic adoptor. Right: Guided missiles CM installation with MAS transmitter, RBK receiver, and RBW panoramic adaptor.

In preparation for the great assault on Normandy more than forty ships were equipped with guided missile jamming equipment—some of the larger units with high-powered equipment and other ships with smaller jammers capable of protecting the ship on which installed. The Germans used radio-controlled bombs—both HS293 and FX—against forces off the Normandy beaches, although not in the quantity expected. In the several attacks which did take place—mostly at night—one ship, a U.S. destroyer, was reported hit by radio-controlled missiles.

LST, hit by radio-controlled bombs, is hopelessly wrecked.

For the invasion of Southern France it was realized that an enormous amount of Allied shipping would be operating literally under the noses of the air bases of glider bomb squadrons. Until these bases were captured or neutralized the danger of attack would be considerable. For that reason more than sixty United States and British ships participating in the assault were jammer equipped. Extensive training exercises were conducted prior to D day, and specific instructions for monitoring, jamming, and alerting were incorporated in the operation plan.

Four attacks were made against the Southern France beachhead during the first four days after the landings. Of approximately twenty bombs launched one hit a U.S. LST.

The battered Luftwaffe did not use the radio-controlled bomb after August 19, 1944, probably for a combination of reasons that include its vulnerability to jamming. V-1 and V-2 bombs, incidentally, were not radio-controlled so there was no jamming problem or possibility on that score.

SUCCESSFUL JAMMING ISN’T EASY

Make no mistake about it, the FX and HS293 bombs—which incidentally used the same receiving and transmitting control equipment—were extraordinary pieces of equipment. The radio control mechanisms were extremely well designed. Jamming was not easy. The receiving antenna on the bomb was so loaded as to discriminate sharply against signals from surface transmitters (enemy) and in favor of signals from above its own level (position of the controlling plane). Not only must the jammer be operated very nearly exactly on the carrier frequency of the control transmitter but also the jammer modulation must be set to within of one of the control modulating frequencies. The time of flight of the bomb was usually less than a minute; jammer operators were trained to intercept and jam within fifteen seconds after the signal appeared.

Although a careful watch was kept for a shift in operating frequencies, there is no evidence of frequencies having been used outside of the 48-50 Mc band. A complete set of captured transmitter crystals showed twenty operating frequencies spaced 100 kc apart from 48.1 to 50 Mc. In an ordinary VHF receiver capable of covering this band the signal received is a sturdy S-5 if the attacking plane is anywhere above the horizon (in fact, control signals have been heard over distances greater than 100 miles). The control signal is modulated by two pairs of tones, 1000 and 1500 cycles for horizontal control, and 8 and 12 kc. for elevation control. The 8 and 12 kc. tones will not, of course, be heard in the ordinary receiver. The 1000 and 1500 cycle tone alternate at a rate of about 10 times per second, one or the other dominating depending on whether the missile is being turned to the left or right.

The possibility that the Japs might use radio-controlled bombs was provided for, although no operational use was reported. Three Pacific destroyer escorts were fitted with investigational and jamming gear as a precautionary measure.

Meanwhile, research is still being conducted on countermeasures to protect the Fleet against any guided missiles which any future enemy might attempt to use.

They didn’t seem to have much of an idea about what the Hs-293 missiles looked like, did they? They look more like sub-scale B-17’s with a jet engine on the bottom of them in the drawing of one under the Do-217’s wing.

Although, if you were drawing one based on this photo, that’s about what it might end up looking like:

http://www.ausairpower.net/Do-217K-Hs-293A-1.jpg

Great blog!

The technical experts and engineers who worked on these early electronic countermeasures in WWII don’t get enough recognition.